Stop branding everything like it's a candy bar!

6 minute read

What do most branding experts have in common? The information they share on branding nearly always assumes the context of FMCG (fast-moving consumer goods) brands. While the advice they share is indeed valuable, not making this highly specific context of their advice known upfront often misleads marketers into accepting their information as end-all-be-all branding truths. Some FMCG branding advice applies across various categories, however, knowing which elements to embrace and which ones to dismiss will be the difference between success and failure.

Why the bias towards FMCG?

1) The concept of branding (in a commercial context) originated from FMCG.

FMCG conglomerates pioneered the idea of branding in a commercial context. The first-mover advantage made them the ones to spread the knowledge of it, which ultimately became accepted as the general wisdom, even though branding has evolved long past this fixed point in time. This was a period when barriers to entry in business were high and the competitive spots were mostly reserved for the wealthy and powerful. Branding, even advertising, wasn't as broadly used as it is today. Only a few industries took part in it, and FMCG was among the biggest ones. Because the economy was so limited, most marketing practitioners who passed their knowledge onto modern-day marketers were B2C marketers employed by big FMCG brands. External agencies at that time also focused on serving FMCG brands.

2) Advertisers and research institutions have a vested interest in having the FMCG branding practices applied across other categories.

FMCG is defined by high advertising spending. It is consistently among the top spenders across industries, year over year. This trend has remained stable for decades and even during COVID. It's in advertisers' best interest to have brands spend as much money as possible on advertising, even when spending more is not the best course of action for the brand. On the researchers' side of this equation, there have been studies that further this agenda - the most noteworthy discovery being a marketing metric called "Share of Voice". Share of Voice is summarized like this: brands that spend the most money will win the most market share. Despite there being countless signals that infer brand health and future growth (which we cover in Share of Everything), the industry has stuck to the idea of the highest spender, which makes for a strong case in our theory of vested interest.

Brand success drivers in FMCG

The stronger the FMCG brand success driver, the more commonly it appears across books, marketing TEDx talks, and so forth - which ultimately leads to that advice becoming generic. This list is NOT exhaustive.

1) Packaging design / creative

FMCG products are often referred to as "products that have to sell themselves" by marketers. This reputation is rooted in the fact that packaging design can often be the first and last brand touchpoint. This sensory constraint is why packaging design is crucial to physical products and not so important for "intangible" product types (such as consulting). Packaging design must be interesting enough to stand out on crowded shelves and capture the attention of a shopper. Additionally, packaging design has to have been consistent enough over the years to become an instantly recognizable, distinctive brand asset, used to help shoppers easily find the brand they prefer on the shelf. Distinctive brand assets can sometimes reach their ultimate form and transcend into becoming cult icons. Some brands can re-release those iconic products with iconic packaging and sell them over and over again based on nothing but customer nostalgia and emotional attachments they have formed with the brand over time.

Unless consumers are already familiar with the brand, they won't know what to expect from its products - which makes them hesitant to buy. Packaging design serves as a signaling device made to offset this information deficiency by stimulating the consumers' minds through visual cues. FMCG brands will employ colors, shapes, art styles, etc. in the packaging design to tap into consumers' subconscious and successfully communicate the nonverbal brand message. We won't go deep into the nuances of design, but there is science behind why we associate red with strawberry, yellow with lemon, or gritty imagery with energy drinks.

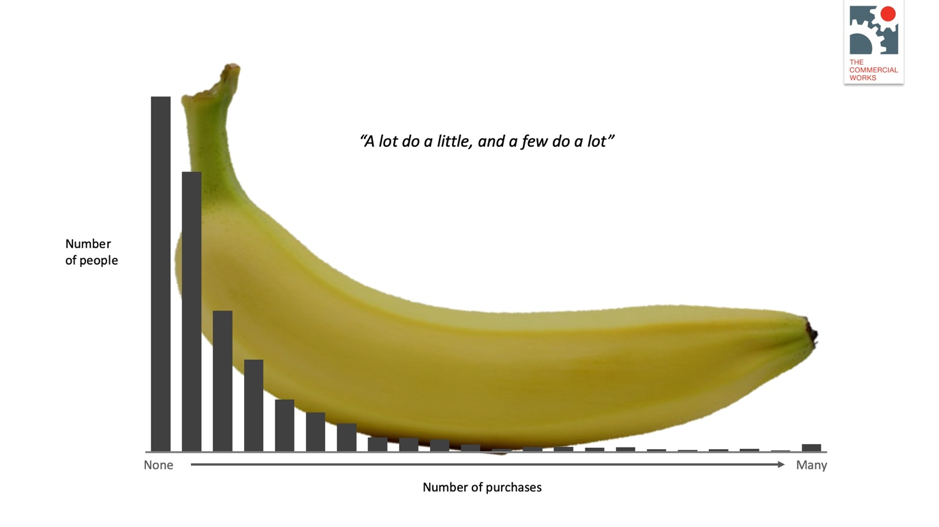

2) Prioritization of casual buyers (a.k.a. Negative Binomial Distribution)

Image credits: Wiemer Snijders

Casual buyers are the overwhelming majority of the FMCG category and make for >60% of any FMCG brand's total sales in any given year. The biggest FMCG brands are the ones that are bought by the most casual buyers in the category. This pattern dictates the general direction of FMCG brands' strategies: sell to the masses, distribute your products as broadly as you can, and be distinctive.

This success driver is caused by the dynamics that inherently define FMCG products: they are products with weak price elasticity, quickly consumed, easily replaceable, low risk, or often impulse purchase decisions of items sold in large volumes. Compare these FMCG dynamics to a category such as high-tech military equipment and you will easily conclude why applying this strategy is smart if your brand is an FMCG brand and not so smart if it's the latter.

3) Expensive and consistent advertising

We have mentioned that FMCG is defined by heavy advertising spending. Unlike some other categories such as B2B SaaS, there are no dedicated salespeople in FMCG. FMCG brands have to optimize their advertising to do all the selling, which makes advertising a bare minimum for competing in this space. The standards for their advertising quality are significantly higher, and by default, more expensive. The second explanation is that FMCG brands are expensive to operate. Significant money must be made to offset the large overhead and justify being in the business. FMCG brands live by the "go big or go home" mantra, which is then reflected in their advertising spend. Economies of scale are a major part of the category dynamics we described earlier. Unlike some other categories where selling one product for a large amount of money can be enough, there is no such thing in FMCG. They can only sell many products at a low price. Unless an FMCG brand is reaching, and thus selling to many (casual) consumers, it won't last. Advertising consistently, creatively, and ultimately reaching many people is how they make that happen. Lastly, this explanation synergizes with the previous section on casual buyers, bringing everything into a full circle.

Branding in FMCG vs non-FMCG categories

Knowing the context in which your brand exists is very important - your category is one of the key factors that comprise this context. We will provide examples of multiple categories, and how their context determines what branding should focus on and why. The side-by-side comparison will shed a light on why applying a one-size-fits-all branding approach would be a recipe for disaster.

| PRODUCT CATEGORY | CATEGORY DYNAMICS | BRANDING PRIORITIES | WHY ARE THESE PRIORITIES? |

|

Enterprise-grade B2B SaaS |

Long sales cycles. |

Branding must focus on building trust. One way to achieve this is through positive reviews and endorsements. Brand messaging strategy needs to be deep and advanced to address the complexity surrounding the product. |

Because this is an expensive, risky purchase decision with many individuals involved. The sheer complexity requires the brand to appeal to multiple people as the overall best choice. |

| FMCG |

Short sales cycles. |

Broad distribution. Emphasis on packaging design and making the brand stand out on the shelf. Different product lines often require a brand portfolio, rather than having all the products under the same brand. |

Broad distribution matters because the product's alternatives are very easy to find, because the product is bought often and because casual buyers won't go out their way to search for a specific brand. Packaging must stand out because it's the only competitive tool brand has at the moment of consumer's purchase decision. |

| "Streetwear" (high-end urban fashion) | Treated as a status symbol. Becoming successful heavily depends on the cultural acceptance of the brand. Brand perception is one of the most important purchase factors. |

Deliberately create scarcity. These products have higher price elasticity and their value appreciates over time. Strategic collaborations with high-status corporate brands or individuals (e.g. athletes, singers, actors...). Deep insight into the cultural climate of the brand's target market. |

Communication between brands and consumers in this category is almost entirely nonverbal. Signals such as high price tag, limited one-off product releases, and collaborations with high-status celebrities manage to signal successfully. The consumer communities in this category can easily tell which brand is authentic in what it claims to stand for and which brand isn't. The latter will be rejected by consumers. |

The cost of ignoring context / The verdict

There is no off-the-shelf strategy for brand growth. Business leaders must resist the tempting siren's call of applying common (FMCG) branding wisdom to the unique context of their brands. Marketers must be more eager to call out the disinformation and encourage more critical thinking. There should be more emphasis on asking questions instead of giving prepared, template answers. Less talk about branding icons of the past and more attempts to create icons of our own. This is a dangerous problem that is, sadly, very prominent in our industry. Despite all of this, one of the most commonly asked questions on Quora is "What's the best brand strategy for a brand in <insert industry name>?".

Ignoring context results in money wasted, time lost, business partnerships damaged, or worse. Ignoring context is not strategic - it's everything opposite of strategy. Luckily, your opportunity lies in the fact that most of your competition is doing the same thing. The winning brands across categories won't necessarily be the ones that have the most cutting-edge product or the highest ad spend. We predict the leaders will be the brands that employ good old-fashioned strategic thinking - a lost art in our fast-paced world. Will that be you?

BrandOps is a unified brand tracking and measurement platform that provides marketing leaders with a continuous view of marketing performance and pinpoints areas that need improvement.